It started with a tweet from my colleague Angela from Mobycon in the Netherlands the other day:

Happy to read less and less children are injured or dead on our roads. A big 'thank you' to all who contributed to that! #safety #NL

That sounded great. She sent me the link to the research and I saw that it was another colleague, Theo Zeegers, from the Fietsersbond - the Dutch National Cycling Organisation who was the author. He was kind enough to translate his article into English.

Theo - like the Fietsersbond in general - is a wonderfully rational person and one of the leading minds on the science of cycling and of bicycle helmets. He's always an inspiration to talk to. Basically, as you'll read below, casualities among child cyclists in The Netherlands is at an all-time low. It's often difficult to penetrate the dark cloud of The Culture of Fear with rationality but Theo does so here. Bear in mind that helmets are virtually non-existent in The Netherlands. The Dutch know more than any other nation on earth that safe infrastructure and traffic calming are the only way to improve cycling conditions, save lives and to encourage people to ride bicycles.Casualties Among Child Cyclists The Netherlands - The facts

by Theo Zeegers, Traffic Consultant, Dutch Cyclists’ Union (Fietsersbond)

Introduction

The debate about the safety of children on bicycles erupts frequently in the media. Usually it is implicitly assumed that children on bicycles are highly vulnerable. The figures indicate that this is not the case. Hence for future use I list the relevant facts on casualty numbers for young cyclists in the Netherlands. The source is the database of COGNOS SWOV. In all cases, the actual (elevated) numbers are mentioned. As a result, there would be no (strong) effect due to the problem of under-registration. I will consider both age 0-11 (children) and age 12 t / m 17 (youth). I use the most current data where available. As a consequence, data on fatalities date from 2010, where those on severely injured dated 2009.Fatality

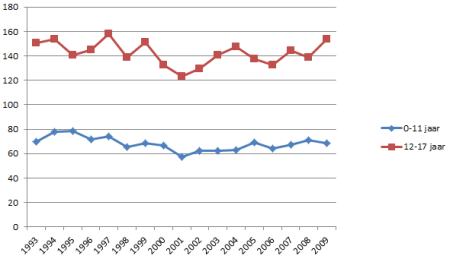

Contrary to popular belief, the number of fatalities among young cyclists is low. In 2010, two cyclists in the age group 0-11 years and 13 from the age group 12-17 were killed in traffic. That is 1% and 8% of all bicycle fatalities in 2010. That is historically low. Graph 1 shows the trend in the number of fatalities among cyclists children over the last 15 years in absolute terms, graph 2 in relative terms. It is clear that there is a particularly strong downward trend over this period. Especially for children under 12 years, the results are so good that further improvement are unrealistic. Graph 1: Trend in fatal bicycle victims (absolute) over the years for the age classes 0-11 years and 12-17 years.

Graph 2: Trend in fatal bicycle victims (relative to all cyclist fatalities) over the years for the age classes 0-11 years and 12-17 years. One might assume that the decrease among the victims of cycling children is caused by the fact that children cycle less and less. The statistics on mobility in The Netherlands do not support this hypothesis. According to these statistics bicycle use increased between 2005 and 2010 among children and adolescents even slightly (MON, Ovin, CBS (2)).

Graph 1: Trend in fatal bicycle victims (absolute) over the years for the age classes 0-11 years and 12-17 years.

Graph 2: Trend in fatal bicycle victims (relative to all cyclist fatalities) over the years for the age classes 0-11 years and 12-17 years. One might assume that the decrease among the victims of cycling children is caused by the fact that children cycle less and less. The statistics on mobility in The Netherlands do not support this hypothesis. According to these statistics bicycle use increased between 2005 and 2010 among children and adolescents even slightly (MON, Ovin, CBS (2)).

Casualties in hospital

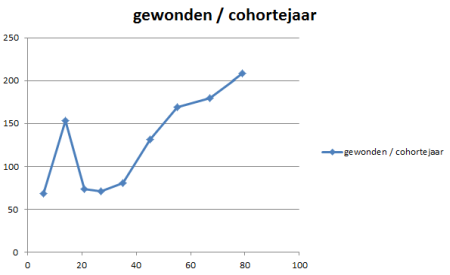

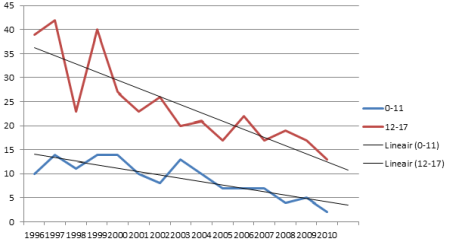

Graph 3 shows the distribution in the number of hospital casualties among cyclists for different ages. What stands out immediately is that the number of victims rises from 40 years on and that there is an isolated peak for young people between 12 and 18 years. The latter peak is attributed to the high bicycle use in that age group. Youngsters cycling about three times as more as children (CBS, 2010). Closer examination shows that the number of casualties among children under 11 years are the lowest of all ages. Again, children appear again particularly low scoring in the statistics! Graph 3: Number of hospital casualties over the different age cohorts. X-axis: age in years. Y-axis: number of hospitalized casualties per cohort year. The trend over the last 15 years is shown in Graph 4. There is hardly a trend, until 2001 there was a slight decline followed by a similarly weak increase. Chart 4: Trend of the number of hospital casualties among younger cyclists over the last 15 years. X-axis: years. Y-axis: number of hospitalized victims per cohort year.Conclusions

The number of fatalities among younger cyclists is strikingly low and this number drops significantly. The number of hospitalized casualties among children (until 11 years) is low. The number of hospitalized casualties among youngsters (12 to 17 years) is high, which can be explained by the high bicycle use in these age classes. Over the years, there is hardly a trend: in recent years may be a slight increase. --- Thanks to Theo for the translation. Cities and nations have a choice. Either they put their faith in car-centric ideology or they boldly step into the New Millenium and starting designing their cities for people instead of machines.If you haven't read about the Fietsersbond's idea for airbags on the outside of cars - placing responsibility in the correct place - read it here.

Here is some contrast to show how twisted things can get when you don't take science seriously and are hopelessly glued to an old-fashioned, last century mentality.There was a study released in a medical journal recently - from near the bottom of the third division of the medical journal leagues - about how helmet promotion for kids has had a whopping result in reduction of head injuries in Sweden. Here's an abstract.

What the paper doesn't tell you - or any of the Swedish press covereage - is that the number of children cycling in Sweden is falling. From over 80% in 1988 to 40% in 2009.

And here in Denmark, we're seeing the same negative trend. The number of children cycling to school has fallen 30% over the past 15 years. In addition, the number of children being dropped off at school in cars has risen 200% over the past 30 years.The City of Copenhagen's Traffic Dept did an internal study a while back, looking at the body of science about helmets and came to the same conclusion of most European cycling NGOs - that the science is divided and the negative effects outweith the positive. They used Thomas Krag Mobility Advice to assist them with the study.

The Danish Cyclists' Federation, who also run the so-called Cycling Embassy of Denmark, have alienated themselves from most other national cycling NGOs in Europe by willingly promoting bicycle helmets, together with the car-centric Road Safety Council. This featured in their membership magazine recently: The difference between the Danish Cyclists' Federation / Road Safety Council and other European NGOs is that they don't have any qualified researchers employed. If you're looking for the face of the Virgin Mary in your tea leaves, you'll probably end up seeing it at some point. They happily quote a study from The Danish Accident Investigation Board, without knowing which individuals provided the "science" on bike helmets in the study is a sign that they they found the Virgin Mary's face smiling back at them. They also trash Dr. Ian Walker's study in the process, and others. Unbelievable. For inspiration in promoting cycling positively and rationally, look to the people who are improving traffic safety and rethinking how are cities should be designed instead of organisations who are scaring people off of bicycles and happily stoking the fire of the Culture of Fear and worshipping at the alter of the automotive status quo. Look to the Dutch and other cycling NGOs in Europe. Ignore the pretenders. Addendum:

Later in the day after writing this I read the .pdf OECD report: "Cycling Safety: Key Messages - International Transport Forum - Working Group on Cycling Safety". The International Transport Forum at the OECD is an intergovernmental organisation with 54 member countries. It's a dry, sober report as one would expect from the OECD but it presents a very interesting view about helmet promotion and legislation.

Helmet usage reduces the severity of head injuries cycle crashes but may lead to compensating behaviour that otherwise erodes safety gains. One area that has received vigorous research focus is on the safety impact of bicycle helmet usage and helmet-wearing mandates. As discussed below, these two must be treated separately. Studies addressing the safety impact of helmets can generally be split into two groups: those that focus on the way in which bicycle helmets change the injury risk for individual cyclists in case of a crash and those that focuses on the generalised safety effect of introducing measures (typically campaigns and/or legislation) to increase helmet usage among cyclist. The first group generally finds that wearing a bicycle helmet reduces the risk of sustaining a head injury in a crash (head injuries are among the most severe outcomes of cycle crashes) though recent reanalysis of previous studies suggests that this effect is less than previously thought (Elvik, 2011). (Ed.: Cyclists with helmets have 14% greater chance of getting into an accident, says Elvik. ) To be clear -- these studies indicate the possible reduced risk of head injury for a single cyclist in case of an accident. The effects must not be mistaken for the safety effects of mandatory helmet legislation or other measures to enhance helmet usage. The safety effect of mandatory helmet legislation as such has been evaluated in far lesser studies than the individual risk in case of an accident. The safety effect of mandatory helmet legislation is a result of a series of factors: - reduced injury risk (due to increased helmet usage) - increased crash risk (due to an often claimed change in behaviour amongst cyclists who take up wearing helmet) - less cycling (leading to a reduced number of accidents and injuries, but also to a - higher accident risk for those who still bike)

Whether bicyclists change behaviour, when they start to use a bicycle helmet seems very uncertain (and difficult to prove), but it is evident that mandatory helmet use might reduce the total number of bicyclists. It is also possible that cyclists who continue to bike might represent a behaviour which is different from the behaviour of those who stop biking. In the end this could very well lead to an overall change in behaviour.